Assessment in the Maritime – Skills Versus Knowledge

Dec 16, 2015 Murray Goldberg 1 AssessmentThe following post is part of a series of articles originally written by Murray Goldberg for Maritime Professional (found here). We have decided to re-post the entire series based on reader feedback.

Introduction

This is a continuation of a series of articles on assessment in the maritime industry, the previous article can be found here. This particular post looks at one of the most basic aspects of creating effective assessments: the difference between skills and knowledge. We need to give this serious thought as a basic element of assessment planning.

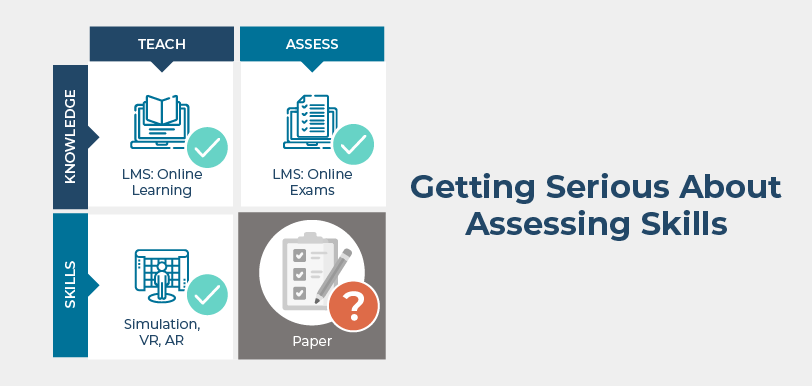

Given the importance of skills (and therefore our focus on them) in the maritime industry, it is not always obvious what role knowledge plays. It is important to clarify the distinction between skills and knowledge not only because this will guide our assessment topics, but also because different assessment techniques are required for testing skills and knowledge. For example, skill assessment requires techniques such as demonstrative exams (“show me how to …”), or simulation-based assessment. Knowledge assessment is very different. In that case, objective exams, including multiple choice tests, can be very effective in measuring knowledge.

Read on to understand the difference between knowledge and skills, how one influences the other, and the relative importance of each in the maritime industry.

The Need to Assess Knowledge in Addition to Skills

When most of us think about assessment in the maritime industry, the first thing that comes to mind is skill assessment. Can the officer or crew-member safely perform the skills required of them? Can the quartermaster steer the ship? Can the engineer perform the required mechanical maintenance?

As these are the first thoughts that come to mind, we tend to organize our assessments around the evaluation of skills. After all, if everyone performs their necessary skills correctly, what more is needed?

The Research

Let’s see what the experts have to say on this topic:

“A study by the U.S. Coast Guard found many areas where the industry can improve safety and performance … the three largest problems were fatigue, inadequate communication … and inadequate technical knowledge.”

Human Error and Marine Safety – U.S. Coast Guard Research & Development Center

“Knowledge-based mistakes may occur when we have to think our way through a novel situation for which we do not have a procedure or “rule”. … Knowledge-based … mistakes by crew members account for 13% [of maritime accidents].”

Searching for the Root Causes of Maritime Casualties – Maritime Research Centre, Warsash, Southampton, UK

You’ll be interested to know that the study from which the second quote was taken notes that “skill-based” mistakes account for 9% of accidents. Fewer than “knowledge-based” mistakes!

Knowledge – the Foundation of all Skills

But some argue that it is not necessary to assess knowledge separately. After all, it is the skills that are the end goal. If the mariner can perform any task skillfully – does that not mean that they already possess all required knowledge to perform that skill? And if that is true, once we test the skill, what is the point of testing the knowledge?

First, as everyone will recognize, it is impossible to fully assess any candidate’s skills. We cannot assess performance in every scenario, contingency and context that a mariner will face during their career. We can and should attempt to cover a broad range of these, but we will always fall short of completeness. How do we assess their ability to perform in novel situations then – ones which we cannot directly test?

To answer this, look at the second quote above, from the Maritime Research Center. It says: “Knowledge-based mistakes may occur when we have to think our way through a novel situation for which we do not have a procedure or ‘rule’”.

At the heart of this statement is the fact that underlying every skill is a set of knowledge on which that skill is built. We can teach a monkey how to perform a skill under conditions which never change. However, as soon as conditions vary, only a human with both knowledge and the ability to reason can make intelligent decisions to perform the skill correctly and safely. The deeper the knowledge, the more readily adaptable the person is to more widely fluctuating conditions.

This is especially important in light of the ever-increasing complexity of vessel-based systems and the complex knowledge required of modern mariners. Understanding “how” to perform some task without understanding the systems which underlie the task creates a safety risk.

How does understanding the underlying systems help?

- An understanding will help inform the mariner the consequences that arise when the task is not performed or is incorrectly performed. Having this knowledge creates a critical incentive to conscientious (and therefore safe) performance.

- An understanding will help mariners make intelligent decisions when presented with unexpected equipment operation, unexpected readings, or a novel emergency situation.

Despite our best efforts, we cannot train and assess for every situation. Nor is it possible to train and assess motivation into a candidate. The next best thing we can do is to train and assess the knowledge which will help motivate mariners to do their job well, and to provide them with the necessary tools to react intelligently when an unexpected situation arises. This is the age of the “knowledge worker” – and the maritime industry has entered this age. We need to prepare them for the job. Safety depends on it.

Both Knowledge and Skills Assessment is Important

If you are not convinced that knowledge training and assessment (in addition to skill training and assessment) is both:

- Important, and

- Often not given the weight it deserves,

then look at this quote from the National Academy of Engineering and the National Research Council study “Interim Report on Causes of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Rig Blowout and Ways to Prevent Such Events”:

“Personnel on the Deepwater Horizon MODU were mostly trained on the job, and this training was supplemented with limited short courses …. While this appears to be consistent with industry standard practice … it is not consistent with other safety-critical industries…

The failures and missed indications of hazard were not isolated events … [this] raise[s] questions about the adequacy of operating knowledge on the part of key personnel.”

It is very interesting to me how they conclude that the training was not consistent with other safety-critical industries.

For 10 years I was a faculty member at the University of British Columbia. There, one of the courses I taught covered safety-critical software systems. The techniques taught for systems where software, if it malfunctioned, could put humans at risk, were quite different than for other systems. A tremendous degree of oversight, evaluation and testing was applied – not only to the software, but also to the processes under which the software was created. Safety-critical activities require a higher order of training and assessment.

The maritime industry is a safety-critical industry with increasingly complex knowledge requirements. Knowledge, not just skills, must be taught and assessed.

Conclusion

So – which is more important to assess – knowledge or skills?

Clearly both need to be assessed.

If you are only assessing skills, you are compromising safety when crew-members encounter unexpected situations – as will always be the case. You are also creating a motivational issue because workers will not fully appreciate the consequences of failure to perform. If you are only assessing knowledge, you are missing a critical aspect of performance testing.

Both components require different assessment techniques – a topic that will be covered in upcoming posts. Please “Follow this blog”, below, to be informed of these articles as they are released.

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.

Great article and good insight, Murray!

Even though critical performance is essential to be measured, also underpinning knowledge and understanding is crucial for decision-making and for understanding the consequences of a certain action.

The industry encounters numerous issues where, for instance during dynamic positioning, an operational vessel suffers a loss of integrity due to actions by non-DP staff on board (maintenance work, electrical work) who fail to see the bigger picture, while they execute their physical task perfectly. A focus area for sure!

It is important however that there remains correct focus during assessments and that in determining pass/fail a theoretical test cannot compensate for lack of critical practical skills.

Also testing knowledge and understanding should not depend on the ability to read and interpret English ‘on a governmental level’ (unless that is the actual objective) since the English language is non-native to most seafarers.

In computer-based or written tests one should not be testing the level of mastery of the English language but the correct insight in a certain topic. This means that setting correct questions, answers and distractors requires very much attention and that they are aimed at the target group. Keep up the good work!

Ruud de Bruin – DNV GL SeaSkill