Tips for Writing Better Multiple Choice Questions

Jul 27, 2016 Murray Goldberg 0 Assessment, Multiple Choice, TipsIntroduction

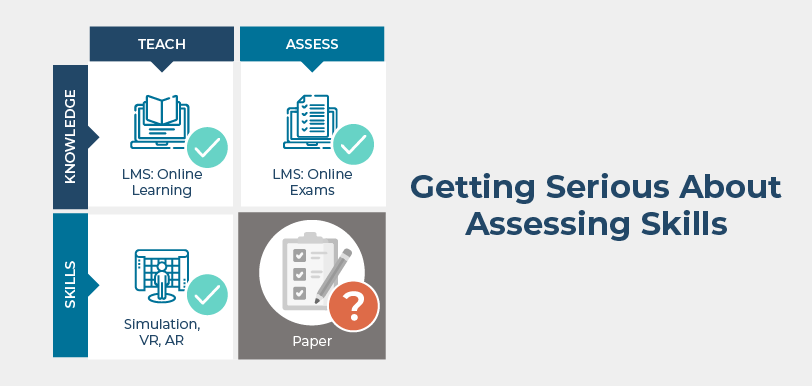

In the previous articles of this series (here and here) I began a discussion on the use of multiple choice questions (MCQs) in maritime assessment. Although widely used, MCQ tests are also one of the most highly criticised. However, written carefully and used appropriately as one part of a multidimensional assessment program, MCQs can be a real asset to maritime assessment.

My first article covered some of the pros and cons of MCQs. The second article looked at some important guidelines when using MCQs. This final article in the series attempts to provide some practical tips on how to write effective and useful MCQs.

Tips for Writing “Good” Multiple Choice Questions

I have had the misfortune of seeing more poor implementations and uses of multiple choice questions than I have good ones. This does not have to be the case: used properly, MCQs have benefits that other assessment techniques do not possess. Each assessment technique has strengths and limitations. By combining techniques, a comprehensive assessment program can take advantage of the diversity of strengths and accommodate the limitations of individual techniques. If we leave MCQs out of the equation, we are missing their strengths.

So – how do we write and use them well?

Tip #0: Never use MCQs as the sole assessment technique.

This was already covered in depth in the previous article, however, this is such an important point that I could not write an article on MCQs without making this statement. If you have not read the previous article, please do so now to understand this important tip.

Tip #1: Randomize questions and supervise tests.

I was in a conversation with a training manager at an OSV operator who was describing a problem they had: their employees were using a CBT (computer based training program), but did not seem to be learning the knowledge required. Employees would sit down at the computer, proceed straight to the MCQ assessment, and then pull out a piece of paper. They would then answer the questions using the answers on their piece of paper.

It turns out that their CBT had been in use for a number of years and presented the exact same series of questions each time an assessment was delivered. There are two problems here.

First, the trainees were allowed to complete the assessment without a trainer or supervisor present. This gave them the opportunity to copy down the questions and answers, determine the correct choices, and then share them with the rest of the crew. Trainees should generally not be allowed to complete or review their assessment without some authority present. No matter what kind of assessment technique you use, MCQ included, supervision is always a requirement.

The second problem is that the same assessment should never be used more than once. If randomized, it is impossible for correct answers to be shared with others since future trainees will receive different assessments. Fortunately, most modern learning management systems provide randomized examinations. As an example, in an LMS there is a database of MCQs, with each question belonging to a category. There may be 50 questions in each of 10 categories, with each category corresponding to a required competency. Each time a trainee sits down to write an exam, a number of questions (let’s say 5) are randomly selected from each of the 10 categories. In this way, each trainee receives a unique 50-question exam which covers all competencies. Each test will all have a different mix of questions presented in a different order. This greatly reduces the possibility of answer sharing.

Tip #2: Gather feedback, review, and then update.

All of BC Ferries’ 15,000 questions in their LMS database were written by subject matter experts. Yet even so, when a new question is first used, there is a pretty good probability that it is not yet perfect. In general, 1 in 10 questions needs some revision after it is first written. But how do we get to the point where questions are well written and unambiguous?

We have found that the most effective way of doing this is to engage the entire community in vetting questions. In practice, this means that trainers and trainees are encouraged to provide feedback on every question they encounter. Simple mechanisms are used to allow them to provide feedback and to allow the training managers to update the questions based on the feedback.

To this end, an LMS ensures that there is a feedback icon next to every question in the exam. If the trainer or trainee feels that there is a problem with the question, they simply click the feedback icon, and indicate the problem. The manager is notified and, if necessary, the problem can be addressed.

This simple technique has proven to be one of the most effective and valuable means of ensuring that all of the questions in the database are unambiguous, current, and test an important fact.

Tip #3: Test only one item of knowledge, and decide what that item is before writing the question.

This may seem like a strange bit of advice, but it is critical and often overlooked.

When writing a MCQ, first determine what specific bit of knowledge that the question will test. Decide what common misunderstandings are present and use them as detractors (answer choices which are false). Most importantly, remember that the question is not there to test reading ability and one’s command of the English language, or the ability to avoid “tricks. The question is there to test the one bit of knowledge.

If you write a question which requires knowledge of multiple facts to answer correctly, then a candidate answering incorrectly does not tell you where the gap in knowledge is.

So before sitting down to write your question, decide specifically what single fact will be tested, and vet your question to ensure only that one fact is tested.

Tip #4: Use simple, straightforward language.

As follows from above, if you use complex language, you are testing the candidate’s ability to read and understand complex language. If you want to test this, then do so – but in its own separate question.

By using anything other than very straight-forward language, you are going to create a significant impediment to any candidate whose first language is not English. Many times, apparent cultural differences in exam performance can be attributed to language differences. These can be avoided by using direct and simple language in both the question and answer choices.

Further to this point, avoid the common desire to create “trick” questions – ones whose answer choices can very easily be mistaken for correct or incorrect when they are not. The only time to use such a question is when being able to decipher subtle differences in correctness is important for safe or efficient performance. But otherwise, they unnecessarily complicate the question and test something other than the desired knowledge.

Ask the question directly, simply and unambiguously. List your answer choices with the same clarity.

Tip #5: Use a variety of questions of varying difficulty for the same topic.

For any complex knowledge, it is a good idea to test that knowledge at different levels of depth. For example, some questions should test knowledge of the topic at a high level, others at a more detailed level, and still others should test at a level of high expertise. Doing so ensures that your exam results will give you a good idea as to what depth the knowledge is understood.

The alternative, often mistakenly used, is to use questions which require full understanding to be answered correctly. This yields exams that tend to be done either very well, or very poorly by trainees. This may tell you whether the candidate has the required knowledge, but will not tell you how “close” those who answer incorrectly are to having it.

If you are randomizing tests, be sure to create question categories for each level of question difficulty. This way your exams will contain a balanced mix of easier and more difficult questions.

Tip #6: Construct your answer choices carefully.

There are several pieces of advice here.

First – some basics. Most experts agree that 3-5 answer choices are best. Fewer and it is easy to perform well on the exam by guessing. Too many and it unnecessarily complicates the question.

Second – never user silly answers as detractors. There is no valid reason to do so other than humor. Remember that you are taking up the time of a trainee to read the nonsensical answer when they are in a time-limited situation.

Third – detractors should always consist of common misunderstandings that you do not want to be mistaken for correct answers. There should be a reason for every detractor that is part of the question. For example, if you want to ensure that the trainee knows the overall length of the vessel within a certain tolerance, then the detractors should be plausible choices, but be outside that tolerance.

And finally – be absolutely sure that all of the answer choices (the correct answer and all the detractors) are of roughly the same length, the same detail, and use the same language patterns. It is very common where the correct answer can be picked out simply because it is longer, or uses different phrasing than the incorrect answers.

Conclusion

Writing good MCQ tests is not rocket science, but it does take a little time, knowledge, and feedback to get it right. Once you have a bank of carefully constructed, vetted and guarded questions, you’ll be able to use them long into the future – and can build on them incrementally. They are a valuable resource which should be carefully cultivated.

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.