Maritime Safety Culture and the Broken Windows Theory

Nov 23, 2017 Murray Goldberg 0 maritime safety, Safety CultureIntroduction

The human element as it relates to safety culture is both fascinating and important. Anyone involved in maritime safety needs to have a basic understanding of how human nature influences organizational safety attitudes and performance. This article looks at one important aspect which explains why it is difficult to improve organizational safety cultures.

It’s not all bad news. It turns out that the same human trait that makes cultures hard to improve can also help an organization maintain a healthy safety culture. The trait can be explained by something called the “broken window” theory of human behavior. An understanding of it will help you improve and maintain a healthy safety culture in your organization.

We begin with an explanation of the broken window theory, and then move to a description of how this helps us implement a healthy safety culture in the maritime industry.

The Broken Window Theory

The broken window theory was introduced by two Harvard professors, James Wilson and George Kelling. If you are interested, the full text of their paper can be found here.

You’ll see that the paper is about crime and neighborhood safety. However, the trait identified also influences people in many domains aside from crime. This trait applies to areas from software engineering to maintaining cleanliness and everything in between. It is easy to argue that it also has an effect on organizational safety culture.

So what is the broken window theory?

The broken window theory is basically one of escalation of behavior based on social norms. Using crime as the topic, the theory says that crimes (even comparatively small ones), if not addressed, lead to more and bigger crimes. The converse is also true. If small crimes are addressed quickly, then there will be a reduction in all crimes – including major ones.

The idea is that crime rates are influenced by the perception of what is acceptable in the “community”. If there is a perception that the community will not accept crime of any kind, then crime rates go down. If it seems that the community is accepting of crime (i.e. “everyone does it”), then crime rates go up. This may seem obvious, but there are also some subtle implications.

The cycle is further perpetuated as the perception what is accepted can influence the type of people moving into and out of the community. Using crime rates as an example: when a community is accepting of crime, this tends to cause crime-accepting people to move in, and crime-abhorring people to move out.

The Experiment

In one experiment that illustrates the theory, a car without license plates was placed on a street in an affluent neighborhood in California. It sat untouched for more than a week. After the week had passed, those in charge of the experiment smashed part of the car with a hammer. Within a few hours passersby joined in, destroying the car.

How could this happen in an otherwise low-crime community? Consider the signals that the car “gave off” to the members of the community.

The original car provided a strong social signal: despite the car being abandoned, it was intact and demonstrated to the community that it was unacceptable to destroy it. Similarly, the initial destruction performed by the experimenters caused the car to give off a different social signal. It said that it is socially acceptable to cause damage to an abandoned vehicle. This one signal led to more destruction by a group of people susceptible to the message. Their further destruction created yet a stronger signal, resulting in a cycle which ended in the complete destruction of the car. As Wilson and Kelling put it: “one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares and so breaking more windows costs nothing”. One window leads to two, two lead to four, and so on.

Interestingly, the authors found that the described effect worked even on people who would normally consider themselves law abiding. Many people who were normally law abiding joined in on the destructive action once their community signaled to them that this was acceptable behavior.

The social signals cause escalation not only because community activity spreads to existing community members, but also because such behavior tend to attract others who are already predisposed to similar behavior. Not only is the behavior of the community changed over time, but the composition of the community is changed – from generally law-abiding individuals to those who tend to be less so. This, of course, further perpetuates the negative cycle.

Unlike some theories, this one has a very practical application because it works both ways. Just as social acceptance of crime increases the crime rate, social rejection of crime reduces it. In the 1990’s, New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani enacted a policy whereby small crimes such as transit fare evasion and public drunkenness were targeted aggressively. This sent a strong social signal that crime was not acceptable. The result was that crime across the board fell significantly. And while the broken windows policing alone did not bring down the rates, according to multiple studies, it is likely that it had some role.

What does this tell us about maritime safety culture?

Maritime “Broken Windows”

It is easy to imagine how social signals and acceptable community behavior can apply to improving and maintaining a healthy organizational safety culture. It is all about:

- Defining acceptable community behavior

- Giving community members (employees) the tools they need to conform to community expectations (safety training, well maintained equipment, etc.)

- Signaling that behavior consistently

The first item, defining acceptable community behavior, is comparatively easy. In terms of safety culture, acceptable behavior means things like understanding and being competent at safe operations. It means always doing the safe thing (even when no one is looking). It means identifying and reporting unsafe situations and doing your part to ensure they are corrected, and it means always communicating the safety message to other community members (the people you work with). There is more to this than presented here, but defining safe operations is not generally difficult.

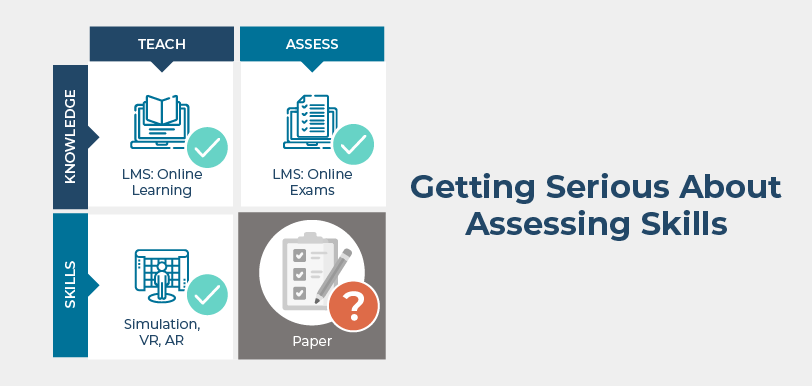

Likewise, the second item is relatively straightforward. You either do it or you don’t. There is no excuse for inadequate training or unsafe equipment or procedures. As mentioned in many of my previous blog posts, there are inexpensive and highly effective training techniques available. A large body of studies exists to inform us on how to train effectively. The use of technology puts cost-effective, high quality training and measurement of results at our fingertips. All that is required is to do a little research in order to understand what works and implement it. It does not have to be difficult or expensive.

Repairing The Broken Windows

It is the last item in the list above that, in many ways, is the most critical.

The broken window theory tells us that in order to improve safety in an organization, it must be clear to each employee that the people they work with (their community) all consider safe operations paramount. In an organization with an unhealthy safety culture, this presents a bit of a chicken and egg problem.

Individuals are unlikely to take safety seriously until the rest of the community does. And the community, by definition, will not take it seriously until each individual does. This is why unsafe cultures are difficult and slow to repair. But it can be done.

The ways in which we can get around this issue were discussed in previous blog posts. But to recap, they include:

- A firm, clear, visible and persistent commitment to safety beginning at the top.

- Clear safety messaging throughout the organization.

- A fair “blame” culture where accidents and near-misses are used as learning opportunities rather than a cause for punishment.

- The identification of safety “ambassadors” throughout the organization.

- A commitment to safety (and therefore each employee) through the implementation of best-practice training.

- Transparent communications between top management and all employees on safety initiatives, successes, shortcomings and safety metrics.

By implementing the practices above, the process of changing safety attitudes among all employees is “bootstrapped”. Employees who are predisposed to safety will absorb the message from management and start to perform more safely. Many of them often become safety ambassadors and demonstrate a commitment to safety to other employees. Theye will influence the next “tier” of safety-minded employees through their actions, drawing them to the message (and acts) of safety. That larger audience will more widely demonstrate that the community is committed to safe operations and that performing in an unsafe way will not be tolerated. Ultimately, the majority of employees will absorb the message.

Now a culture of safe operations exists. It is a community norm. People who can’t adapt will be at odds with their community making them more likely to change their actions, or find employment elsewhere. People who are predisposed to safety will be inclined to seek work at this organization because they will be joining a community with a compatible value system.

Now that safe operations are a community value, the same “broken window” effect tends to make them self-sufficient. As indicated above, people predisposed to safety will be drawn to the organization and, once there, will do things which perpetuate the safety culture. They will perform safely, they will report near misses, they will become safety ambassadors, and so on. Ultimately, some of them will become management who will, in turn, continue to communicate safety and implement policies which perpetuate the safe culture.

Conclusion

The broken window theory explains why unsafe cultures are difficult and slow to change. However, the same theory has a very positive side in that is also explains why companies who have been able to establish a healthy safety culture tend to keep (and improve) it. The theory both provides a lot of guidance for the journey toward safety and helps prepare us for that journey.

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.