The Cost of Simulator Training: Is it Worth it?

Aug 16, 2017 Murray Goldberg 1 Maritime Training, Simulator TrainingIntroduction

For decades, simulation has been a part of maritime bridge and engine room training. But, as with many safety initiatives, its effect is somewhat difficult to quantify.

We all know, intuitively and empirically, that simulator training has value. It extends a trainee’s experience in typical and atypical scenarios. And it provides an avenue for total task simulation in a safe environment. However, while we agree simulator training works, we also know that it comes at a high cost. Simulation training is both expensive to create and maintain. Is the cost worth the benefits?

Most will agree that simulator training is indeed worth the cost. This blog post will examine some research that attempts to derive a concrete return-on-investment (ROI) for simulation. The maritime industry is operating on tighter margins and having statistics to back up our intuition can help when investing in maritime IT and training.

Cost vs. Benefit

One compelling argument applied to safety training in general is that the value of one life saved is greater than any cost – as long as it is affordable. If we believe that simulator training has the potential to save one life, then it is worth any costs associated with it. Therefore, no further analysis is necessary.

However, there are real problems with that line of reasoning.

First, it does not provide us with any basis to compare with other safety initiatives. It may be true that simulator training is worthwhile, but there may exist some other safety initiative that can save more lives at a lower cost. Unless we assess the costs and value of each initiative, we are unable to make informed decisions.

A second issue is that without a cost benefit analysis, implementation decisions can become more emotional than logical. If it can be shown that simulator training actually saves money through a reduction in accident-related costs or performance issues, then perhaps its use would be even more widespread.

This is exactly the question addressed by a very interesting maritime education and training paper given by Capt. Stephen Cross of the Maritime Institute Willem Barentsz. I’ve had the good fortune to meet Capt. Cross. His paper, “Aspects of Simulation in MET – Improving Shipping Safety and Economy”, presents a concrete view of the economic effects of simulator training. The results are compelling.

The Idea

Capt. Cross expressed the motivation of his study as follows:

“If simulator training can improve safety of operations, this would result in fewer accidents, which in turn will save funds, which could be used to afford the additional training efforts.

Additionally, if the amount of the increased costs of training is compared to the funds spent presently on damages from accidents, a simple cost benefit analysis could show if such training efforts are worthwhile”.

The Study

To conduct the deceptively simple cost-benefit analysis, Capt. Cross needed to look at a wide array of information related to the desired objectives, the current conditions of MET and maritime operations. He then had to study the consequences of change. To give you some idea as to the complexity of the study, Capt. Cross proceeded along the following path:

- First he determined what percentage of maritime accidents were attributable to human error.

- Next he determined what percentage of these accidents could be attributed to training shortcomings.

- Next he determined what percentages of competencies could be improved by simulator training.

- Next, he had to determine by how much the above competencies could be improved through simulator training.

Multiplying the percentages together gave an estimate of the reduction in accidents through the use of simulator training. With that information, he could then look at the cost of simulator training to compare it to the cost savings through a reduced number of accidents. His analysis will be summarized below. Please note that in the interest of space, only a portion of Capt. Cross’ analysis can be presented. I encourage you to read the paper for full details and further insight.

Finding the Percentages

Human Error:

Many studies have shown that human error was and continues to be the underlying cause of the majority of maritime incidents. To determine a specific percentage, Capt. Cross looked at the Norwegian DAMA database of accidents for the Safeco project (EU 4th FP, Safeco, 1996). It was shown that from 1981 to 1996, of the 5400 accidents that were included and the 1100 that were fully analysed, 80% could be attributed to human factors while 20% of the accidents were caused by technical factors.

Finding: Human error was the underlying cause of 80% of maritime accidents.

Lack of Sufficient Training:

Looking at how training influences accidents, Capt. Cross looked at a number of studies which evaluated the causes of accidents. Among them he cites three in particular:

The first study, “Accidents at sea: Multiple causes and impossible consequences”, from Wagenaar and Groenegweg found that 35% of accidents were caused by improper training. Another 46% of accidents were due to bad habits, which could be influenced by procedural training. Combining the two gives a total of 81% of accidents that were influenced by training.

A second study from Kinzo Inoue found that 55% of maritime accidents were collisions and another 15% were groundings. Although technical failure could account for a portion of these types of accidents, this also implies that up to 70% of reviewed accidents could have been avoided with better trained personnel.

The last study referred back to the Safeco project. Capt. Cross found that of the human error related accidents, 41% of them indicated a lack of knowledge, skills and attitude, all of which could be improved by training. A further 37% of human error related accidents were due to a lack of operational procedures. Together, this means that 63% of the investigated accidents could have been influenced and possibly partly avoided with better training.

Capt. Cross concludes that “it seems conservatively acceptable to say that from 65% upward of the investigated casualties has relevance to (lack of) sufficient training”.

Finding: A lack of sufficient training could be attributed to 65% of maritime accidents.

Simulator Training Applicability:

Although simulation training is a very thorough training tool, not all competencies needed for safe operations can be taught and practiced with simulation training. Thus the next step was to determine what percentage of competencies were “teachable” via simulator training. Capt. Cross looked at the STCW Code Part A and made a count of the number of competencies or skills, per function and level, where simulators were indicated. This number was then compared to the total number of competencies per function and level to give an approximate percentage of simulator applications. Capt. Cross found that an average of 58% of competencies and skills indicated simulator training.

Finding: 58% of mariner competencies could be taught and practiced with simulator training.

Competency Improvement Through Simulator Training:

Finally, Capt. Cross needed to determine the level of improvement in performance that could be achieved through simulator training.

The study provided simulator training to groups of mariners, both experienced and inexperienced. It then looked comprehensively at the outcomes of exercises for these groups over the time that they were involved in the training. In the end, both groups (experienced and inexperienced) benefited significantly from simulator training. Based on Capt. Cross’ observations, there was an average performance improvement of 45% that could be assumed due to simulator training.

Finding: An average of 45% performance improvement is due to simulator training.

Putting the Numbers Together

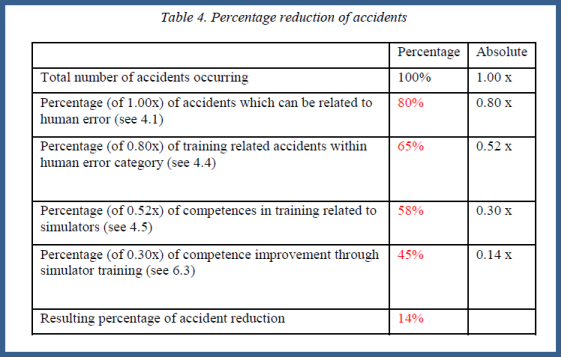

Capt. Cross took the findings above to arrive at a conservative estimate of the accident reduction possible via simulator training. The ultimate result, 14%, is shown in his table below:

Capt. Cross’ analysis has estimated that through the appropriate application of simulator training, 14% of maritime accidents could be avoided. What does this mean for the economics of simulator training versus the cost of accidents?

So – Is it Worth It? The Economics of Simulator Training:

Capt. Cross indicates in his paper that there are many potential cost savings available through improved operations from simulator training, even when ignoring the potential for accidents. But to look at accident costs in particular, he cited the claims history of the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund over the period of its existence. Even though the IOPC Funds claims represent a fraction of the cost of maritime accidents worldwide, they are well documented and thus provide a reliable source of information on accident costs. The results are impressive. According to Capt. Cross:

“Over the 28 year period of [IOPCF] observations used, at least 856 million $US have been claimed for accidents which in some way have a relationship to bridge, engine room or cargo handling procedures. … [A reduction of] 14% related to the simulator training course cost would allow for at least 376,946 “average” student simulator courses to be afforded. As this figure is almost similar to the global officer population it means every officer could be afforded a simulator training course from the avoided accident claim costs of the IOPC Fund relevant accidents.”

So – if the 14% accident reduction estimate is accurate, and it is applied to the relevant IOPC funded accidents, the cost saved could provide every officer in the world with a simulator training course. And since there are far more accidents (and their related costs) than are funded by the IOPC, the conclusion is that simulator training has the effect of both reducing costs and improving safety – a win-win.

Conclusion

Capt. Cross’ analysis is a compelling argument for simulation training as both a cost-saving measure and a safety improvement measure. Even if you find an argument with one or another of the numbers presented in his analysis, one could argue that the “margin of safety” in the analysis is very large. That is, it seems unlikely that his assessment could be so far off as to make simulation training a net cost, as opposed to a net saving.

And even if it were a net cost, as unlikely as that might be, we can go back to the original visceral argument: if one life is saved, the any affordable cost is one well spent.

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.

According to many scientists in the field of human factors and safety systems they claim that human error is never the cause of accidents. ‘Human Error’ is the consequence, it indicates symptoms of trouble deeper inside the organisation. Check websites such as Sidneydekker.com and jbsafety.se and many others for further facts.