The Basics of Assessments and How to Improve Them

Nov 18, 2015 Murray Goldberg 0 Assessment, Maritime TrainingThe following post is part of a series of articles originally written by Murray Goldberg for Maritime Professional (found here). We have decided to re-post the entire series based on reader feedback.

Introduction

We have all seen candidates who “test well” but perform poorly. We’ve also seen candidates who have trouble performing when being assessed, but we know are mariners who can be trusted. Most of the time, the reason this happens is because our methods of assessment are flawed. Wouldn’t it be great if candidate assessment gave us a better idea of how they will perform as mariners?

Captain Jim Wright, from the Southwest Alaska Pilots Association (Retired), took the time to write me a while back. He said:

“Having been involved in simulator assessments of harbor pilots, masters and mates, my impression is that objectivity is the necessary ingredient for equitable performance assessment.”

I love his comment. The question is, how can we introduce objectivity into maritime assessments? It’s actually not all that easy. But there is much we can do.

This is the second in a series of articles presents current and best-practice assessment methods in maritime training, as well as ways to improve objectivity in assessments. This article covers some assessment basics and provides an example of how BC Ferries combines techniques to improve the objectivity of their assessment of candidates. The first article in this series on assessment can be found here. Please follow this blog to be informed of future articles.

Reliability and Validity

First – a quick bit of theory. The heart of assessment boils down to two fundamental assessment goals: assessment reliability and validity.

Reliability

For an assessment to be reliable, it must yield the same results consistently, time after time, given the same input (in this case, the same knowledge or skill level). If you and I know the same set of information, the test will give us equal scores if it is “reliable”. If the assessment device is a bathroom scale and my weight is unchanging, the scale will show me the same number each time I weigh myself. This is reliability.

Validity

Validity is a measure of whether the assessment correctly measures what it has been designed to measure. There are two related components to validity:

- Is the test measuring the thing it is supposed to measure?

For example, some people argue that written exams are sometimes not valid because they test not only knowledge, but they also test the candidate’s writing ability – something the exam was not originally designed to test. In this case, the assessment is invalid because it is not measuring the right “thing”. - Is it yielding a correct measurement?

For example, my bathroom scale may be measuring the right “thing” (my weight), but the result it gives may be inaccurate – showing 145 pounds if I am really 150. In this case it is not providing the correct measurement and is therefore not valid.

After a bit of careful thought, you’ll probably come to the correct realization that reliability is necessary for validity, but you can have a reliability without validity. In other words, you can have a reliable assessment that is not valid. However, a high quality assessment must be both valid and reliable. That is your goal.

How Do We Achieve Reliability and Validity?

This is the $64,000 question, and as I mentioned above, there is both art and science involved. Having said that, let’s look at some of the basic considerations. To do so we will look at some more specific assessment goals.

In the maritime industry, and in most industries where safety is key, assessments should embody the following qualitative attributes as much as practically possible, and to the extent that they do not negate a more important goal. At a minimum, assessments should be:

- Objective: assessment techniques are objective if the views of the person conducting the assessment do not come into play in the results. For example, multiple-choice tests are completely objective. Having a trainer rate a candidate on a scale of 1 through 10 for steering performance may be highly subjective. Subjective assessments are less reliable because they depend on the examiner and different examiners will produce different results.

- Standardized: assessments are standardized if all candidates are assessed on the same knowledge and competencies, using the same assessment techniques. Standardized coverage and techniques are necessary components for reliability.

- Comprehensive: your assessment techniques are comprehensive if they test all required knowledge and competencies. This is also a requirement to achieve reliability.

- Targeted: assessments are targeted if they test specifically the knowledge and skills required, and no more. This is the first half of validity – ensuring that your techniques are not inadvertently testing something which is not required for safe and efficient performance as a mariner.

Unfortunately the goals above are sometimes in conflict with one another. We often need to (partially) give up one assessment goal in order to (partially) achieve the other. Therefore, even if one of the goals given above yields unreliable or invalid results, it is not necessarily the case that we will want to abandon it all together.

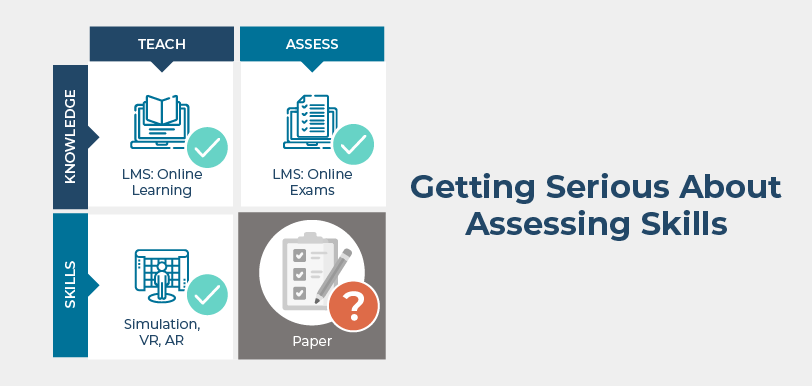

Combining Assessment Techniques

There is a very good argument for combining assessment methods, each of which has different strengths and is designed to achieve different goals. We will discuss this more in a subsequent posting, but for now I’d like to mention a good example of this used by BC Ferries.

BC Ferries has created a new training and education system called the SEA (Standardized Education and Assessment) program. With the SEA program, BC Ferries recognized that it was necessary to make their assessments more standardized and objective. To achieve strict objectivity (a necessary component of reliability), it would be necessary to adopt an assessment technique such as multiple choice exams. A multiple choice exam, although a great tool, when used alone can miss much of what we would like to assess. The physical skills needed for specific job duties, personality traits and communication skills are all difficult to test using multiple choice. On the other hand, multiple choice exams are a very good way of objectively testing knowledge.

Therefore, assessment in the SEA program is multi-modal. It consists of:

- Dynamically-created, randomized and automatically graded multiple-choice exams (delivered by MarineLMS),

- An oral “scenario-based” exam where the candidate is given some scenarios and asked for the appropriate action,

- A set of demonstrative activities where the candidate demonstrates the ability to undertake certain tasks, and

- A meeting/interview with a superior – usually the master.

Some of these are more objective assessments than others, though the ones that are less objective can be made more so – more on that later. Together they provide a body of data on which a quality assessment decision can be based.

Professional Judgement

The goal of assessment in the maritime industry is the determination of whether someone is fit for service, and if not, what remedial action could be applied to make them so. Results such as numeric scores are somewhat arbitrary. It is more important that the scores are reliable and that the assessment covers what it is supposed to test. If so, you and your organization will develop an intuitive understanding of what you can expect from a candidate who scored a 65% vs. an 85% and use that understanding to guide your actions.

Likewise, it must be remembered that exams are tools which yield data, not decisions. Professional judgement, informed by the real data generated by valid and reliable assessments, is required to make a final decision. Just as it would be dangerous for anyone, no matter how experienced, to make an assessment decision in the absence of good data, it is just as dangerous to make assessment decisions strictly “by the numbers”.

You may argue that I’ve just introduced subjectivity into the interpretation of assessment results. This may be paradoxically true, but at some point experienced professional judgement must come into play. Assessments provide data on which this judgement can be based – but one can never rely on numbers alone.

Conclusion

Thinking about these principles and goals in relation to your current training practices, you are likely to find that you are strong on some, and weak on others. More importantly, after ranking the desirability of the attributes above (in addition to any you care to add), you may find that your current assessment techniques are not aligned with your assessment goals. If this is the case, this should be a call to action to achieve alignment. Sadly, that is not always easy.

We will talk more about specific assessment techniques and balancing these often conflicting goals in upcoming articles. Please”follow this blog”, below, to be informed of upcoming articles as they are released.

In the meantime, it’s been a pleasure. Have a great day!

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.